Melville and His MFA by Sea

On the stepping stones to greatness (and why they look like failure)

There has been a recent discourse on Substack about the uses and disuses of an MFA. Do you need one? Is it, actually, bad to have one? Is MFA-literature a genre, in the same way that horror or fantasy, or romance are? Is there a cabal of evil MFAers who are strangling contemporary literature in the cradle by refusing to publish anything other than their narrow circle of friends? Does getting an MFA ruin your writing? And so on.

The true answer—as true answers tend to be—is boring. Having or not having an MFA hardly matters. It hardly matters because an MFA is not a stepping stone to writing great literature. It looks like one, but exactly because it looks like one, it cannot be one.

Brilliant work contains an inherent contradiction. It often does not look like brilliant work (until much later, after we have grown used to it, when we accept its brilliance as obvious and matter-of-fact). In the Penguin Classics edition of Moby-Dick, Andrew Delbanco opens the introduction with this:

Not many years ago, at an elite northeastern university, a prominent English literary critic was asked which was the greatest English novel. The room was paneled and lit by a chandelier, the windows heavily draped, the bookshelves lined with leatherbound classics—furnishings all carefully assembled to replicate an Old World atmosphere. There was not a whiff of sea air in that room. With the combination of eagerness and resentment that sometimes greets the proclamation of a standard, the students leaned forward to hear from their eminent guest. “Middlemarch would be my candidate,” he said, tentatively, “unless by English novel you mean novel in English, in which case it would, of course, be Moby-Dick.”

Herman Melville produced one of the most lauded novels in English, one of the finest American novels ever composed, frequently trotted out as an exemplary candidate for the “great American novel.” Yet, as Delbanco observes, this is somewhat surprising. There is little about both the novel and its author that would suggest its pedigree. It was not evident to everyone at the time. Moby-Dick flopped when it arrived, a fact that depressed Melville so thoroughly he all but gave up writing novels. Because genius does not look like genius, few of Melville’s contemporaries could appreciate the greatness of Moby-Dick. Time was not on their side.

If you could imagine a young person today, say 18-22, who had literary ambitions, who nursed the desire to one day write a “great novel,” how would you recommend they set about that goal? Many people would recommend that they go to college, study English literature or creative writing, perhaps pick up a language or two. That they then go on to get an MFA and perhaps a PhD in comparative literature. Look: we can even ask ChatGPT (which, I suspect, is literally what an eighteen-year-old today would do) and see what it says. It will tell you to do some form of the following:

Read widely, both the classics and novels that are currently winning prizes

Write every day (500 words minimum) and start by writing short stories

Study craft by getting a BA in English or Creative Writing, followed by an MFA; attend workshops, develop a close group of fellow writers

Read the contemporary scene (subscribe to journals like The Paris Review, The New Yorker, Granta, n+1, etc.)

Learn how to revise your work; submit to magazines, agents, and publishers; submit often, learn how to deal with rejection

Mentor other writers

Which is all fine and good, but unlikely to help you write something great. ChatGPT gives you the legible path, which is precisely why it can’t lead anywhere interesting. What this program is designed to do is ensure that you live and work (and perhaps even live and work comfortably) within the prevailing literary scene. If your goal is to become a professor and/or magazine editor and spend your life writing novels and teaching students, this is a clear, actionable plan. However, if you want to write great literature, it might not get you there.

The reason it’s unlikely to work is that the stepping stones to greatness don’t look anything like the final product. Imagine Melville following the similar advice of his time. The program he would have received would have looked quite similar to the one laid out; however, that is not what Melville did. Instead, he spent five years on a whaling vessel. He says, in Moby-Dick, “A whaleship was my Yale College and my Harvard.” A stepping stone to writing a “great American novel” meant not writing at all for five years. Paradoxically, it also meant leaving America, literally stepping off her shores.

If ChatGPT existed in 1840, and if 21-year-old Herman Melville asked it what to do to learn to write great novels, it is highly unlikely it would have recommended signing up for a whaling voyage. At the time, American literature was obsessed with exploring its national identity. Like today, payment for writing was poor, and most who embarked on that path had family money (like Emerson), academic or government posts (like Hawthorne), or struggled in poverty (like Poe). Also, like today, writers were encouraged to contribute to journals and magazines. Editors were courted. Public lectures, book tours, and participation in literary circles were important. It was thought that a budding writer needed to say close to those scenes, centered in Boston, New York, and Philadelphia. Obviously, there were no literary scenes in the South Atlantic Ocean. Even for writers who sought travel for inspiration, boarding a whaling vessel was an idiosyncratic choice. The prevailing expectation was for writers to draw inspiration from classical traditions (which meant embarking on the well-trod European tour) or draw from the domestic and political experiences of their native city—which was usually Boston, New York, or Philadelphia. Melville chose to leave the literary mainstream behind, figuratively and literally.

In hindsight (and, I stress, a particular sort of historical hindsight that not even Melville could have possessed, since he died thinking Moby-Dick was a failure1), we can see that boarding a whaling vessel was exactly what Melville needed to do to write his masterpiece, Moby-Dick. The point is that the steps to greatness do not resemble the endpoint. Boarding a whaling vessel does not look like the path to writing a great American novel, but it was.

In Why Greatness Cannot Be Planned: The Myth of the Objective, authors Kenneth O. Stanley and Joel Lehman demonstrate how ambitious, nebulous goals (like writing a “great novel”) cannot be broken down into clear, legible steps: “The key problem is that the stepping stones that lead to ambitious objectives tend to be pretty strange.” They do not resemble the final outcome. Boarding a whaling vessel is a strange way to write a novel.

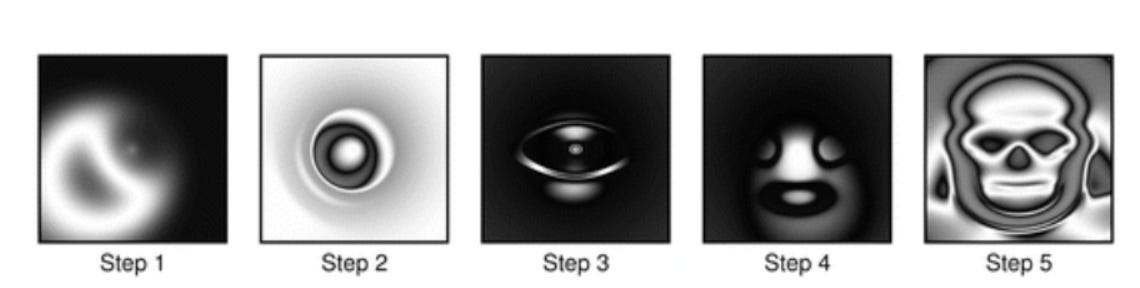

The authors discovered this unintuitive outcome when they built a website called Picbreeder. It worked like a form of artificial selection. Users could create new pictures by breeding them from combinations of pre-existing ones. The “child” pictures would have features from the parents, but, like in selection, would form a new composite. They described it as a form of “genetic art.”

To understand genetic art it helps to think of animal breeding. Imagine that you have a stable of horses. If you’re the breeder, then you can decide which stallions and mares will mate, and eleven months later there will be a new generation of fresh-maned newborns. The important thing is how you choose the parents. For example, if you wanted fast horses, your strategy might be to choose two fast parents to mate. Of course, you don’t have to choose parents only for practical reasons. Maybe you just want the prettiest horses to mate, or the silliest. Whatever the reason, by choosing the parents you influence the children’s genes. They naturally end up a mix of the parents’ genes. In the next generation, when all the children you bred grow up, the process can be repeated. And some of the children might end up even faster or sillier than their parents. Over many generations, the animals evolve in a way that reflects the choices of their breeder.

When breeding genetic art, users might start with an objective. Perhaps they want to create an image of a face or an animal. But the authors discovered that the best way to create interesting images was to have no objective at all: “What turned out to be really surprising is that Picbreeder visitors almost always bred the best images when those images were not their objective.”

Stanley and Lehman ask us to imagine creativity as a kind of search. A writer who wants to write a great novel must search for the idea, and then pull it into existence. But as the Picbreeder users learned, the best ideas are discovered when they are not the focus of the search. This is what happened with Melville. Writing the most interesting novel requires undergoing a series of steps that look nothing like writing an interesting novel. Counter-intuitively, if you set out to write a “great novel,” you are almost certain to fail at it; but if you set out to explore the interesting possibilities of writing, you might, surprisingly, end up with one. More to the point, following a legible series of steps does not bring you closer to writing something interesting. Many writers like to think of their career as a series of expanding opportunities that lead to something “great” and “important”:

You write a poem and place it in a magazine

Another poem wins an award

You start writing stories and place those in magazines, too

You publish a book of stories

You write and publish a first novel

You are highlighted as an “emerging writer,” someone “worth watching”

You publish a second novel; it makes a little more money than the first

You publish a third and a fourth novel; you win a prize and a fellowship

You publish a fifth novel, your magnum opus; money and prizes rain down on you

You spend the rest of your career leisurely writing a sixth and a seventh novel, spending most of your time gardening and appearing on podcasts to discuss, for hours at a time, your “creative process”

You win the Nobel Prize

You die, but for centuries after that, school-aged children are forced to learn how to write by studying your masterpieces

It’s like a satisfying little Matryoshka doll in reverse: each step looks exactly like the previous one, only a little bigger. Unfortunately, this is a trap.

One of the more fascinating images that Picbreeder produced was a skull. What’s interesting is that the skull was not produced by a user looking to produce a skull. In fact, none of the preceding generations of images looked anything like a skull. “One is a crescent shape, another looks like a donut, and another resembles a dish.” To get to the skull required selecting a series of “seemingly unrelated images.”

The problem this demonstrates is that getting to the skull requires breeding a lot of images that don’t look like skulls. Writing a great novel will require doing a lot of things that don’t look anything like writing a great novel (in fact, they will often look like going in the wrong direction). As the authors drill home: “It doesn’t matter how accurately we can assess the Skull-ness of an image because the stepping stones to a good Skull don’t look anything like the Skull anyway. (In fact, this prediction was confirmed in experiments that tried exactly the idea of rewarding Skull-like images, which led to consistent failure.”

If we trace the stepping stones that brought Moby-Dick out of Melville, it reveals a path that no sane writer would choose for their career:

Work as a schoolteacher, clerk, farmhand before going to sea at 21 years old

Spend five years on a whaling voyage and subsequent South Pacific travels

Publish first novel, which becomes a bestseller

Publish second novel, which sells well, but not as well as the first

Publish third, fourth, and fifth novels, each one worse than the last in both financial and critical acclaim

Publish sixth novel to mixed reviews and poor sales; literary reputation in shambles

Publish seventh and eighth novels, both critical and commercial failures; one reviewer even insinuates that you have gone insane

Abandon novels to write short stories

Abandon short stories to write poems

Work as a customs inspector for 20 years to support your family

Die forgotten by the public; last major work sits in a drawer unread and unpublished

Nobody imagines or plans a writing career like this. Melville’s arc is a graph that is consistently down and to the right (we all want something that goes up). But, uh, I’m sorry to report that if your goal is to create something of lasting value (that is read and discussed well after you are gone), then I have some bad news. The path to greatness does not look like little miniature greatness steps. It looks like failure. It looks like you are lost and confused. You probably won’t even see it, won’t even know it happened—because you will be dead.

The MFA promises to turn writing into a series of legible steps. It creates the illusion of progress while simultaneously leading you away from genuine discovery. It promotes the idea of writing as a vocation, as a job like any other. To become a writer is to become a plumber. In both cases, you learn how to do the thing, you get certified, you join an organization that nurtures you, and you get to do more plumbing (sorry, writing) for money. But plumbing and writing are not the same thing. Writing is an art, and art is frustratingly opaque, nebulous, and undefinable. To produce something of value in that field is to follow bizarre, idiosyncratic steps—and see where they lead.

If your goal is to create something great, something of lasting value, you should avoid pursuing objectives that look like legible paths. Instead, you should search for things that are interesting, unique, peculiar. You should pursue novelty for its own sake. It may be helpful to imagine that all great works of art already exist in a giant sequence of rooms. Great artists are great treasure hunters. They find the work that is already there and pull it into existence. If you go where everyone is already obsessively searching, you’re unlikely to find anything, but if you go to the quiet, empty rooms—the places that are under-explored, ignored—well, you just might get lucky.

There’s also a good chance you won’t find anything. Virtually all of us will fail to discover something “great.” We won’t write the century-defining novel or discover a great scientific truth or invent new technology that transforms the world. But that’s ok. Melville failed by most external metrics. Failure might be the point. You won’t know you’re getting any closer to the skull image until the skull image appears. We can still search for what’s interesting. If you find something great, great. If you don’t, well, it will still have been worth it, because you dedicated your life to pursuing your own interests—and that is always worthwhile.

Melville didn’t board the whaling ship because he thought it would lead to writing a great novel. He did so in search of adventure. Like many young people, he was adrift in life, facing limited opportunities and no financial stability. Whaling promised a job (though a grueling and risky one), and it promised something new. It was interesting to Melville.

What seems interesting? Worth pursuing for its own enjoyment? What does Melville’s whaling ship look like to you? Maybe it’s time to board.

A month ago, one of my essays was featured in the Substack publication Return on Attention by Studio Slowcore. It’s one of the most popular things I’ve written; a critique of hustle culture and the “move fast and break things” ethos. Instead, I advocate for a slower, more deliberate pace. If you enjoyed this article, you will probably enjoy this one, too.

Sadly, when Melville died in 1891, Moby-Dick was so far out of the public consciousness that it was misspelled in his obituary as Mobie Dick.

Very Taoist way of thinking, "the legible path is not the true path" is basically the same as "the Way that can be seen is not the true Way"